The Netflix documentary Murder in Monaco has reignited global interest in one of Europe’s most unsettling unsolved-feeling crimes: the 1999 death of billionaire banker Edmond Safra, who was killed in his heavily fortified penthouse in Monaco, a country famed for wealth, surveillance, and security.

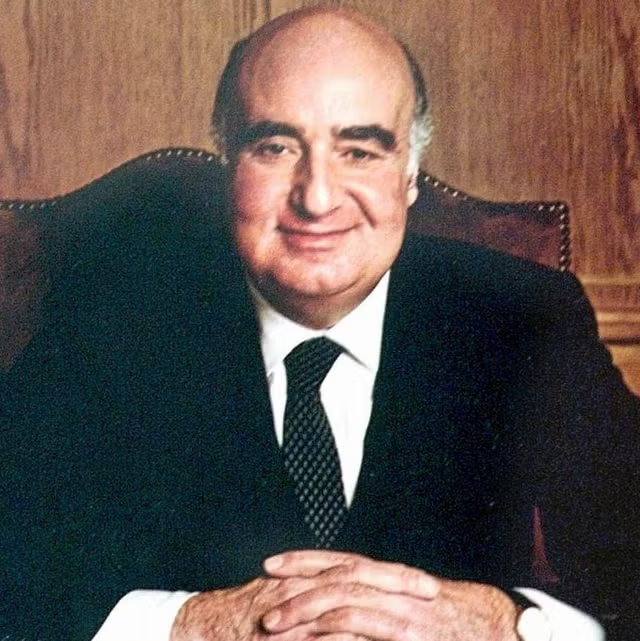

Safra, one of the world’s most influential financiers at the time, was found dead on December 3, 1999, alongside nurse Vivian Torrente, after a fire broke out inside his oceanfront residence. His personal nurse, Ted Maher, survived and was later convicted of murder. Yet, as the documentary carefully lays out, the official narrative has never fully silenced doubts.

Monaco’s reputation makes the case particularly jarring. The principality is often described as one of the safest places on earth, blanketed with CCTV cameras and elite private security. Safra’s penthouse itself functioned like a fortress, guarded around the clock. For many viewers, the central question remains: how could such a crime unfold unnoticed, and why did investigators take more than three hours to enter the apartment after the fire was reported?

Maher claimed throughout his trial that masked intruders—whom he believed were connected to Russian organized crime—forced him into a scheme he did not control. Prosecutors rejected that account, arguing Maher set the fire to position himself as a hero who would “save” his employer. The court accepted the prosecution’s theory, sentencing Maher to prison, despite his consistent claims of innocence.

The documentary highlights troubling details that have fueled skepticism for decades. A senior Monaco judge later suggested the verdict appeared predetermined, while Safra’s brothers publicly accused his widow, Lily Safra, of involvement—allegations never supported by evidence and never resulting in charges. Lily Safra has consistently denied wrongdoing and was never named a suspect.

Legal analysts interviewed in the film point to investigative gaps that would raise red flags today, including limited exploration of alternative suspects and the handling of Maher’s claims that his family had been threatened. “This was a case decided under immense pressure,” one former European prosecutor says in the documentary, noting Monaco’s desire for swift closure amid intense international scrutiny.

Yet Murder in Monaco also complicates any attempt to fully rehabilitate Maher’s image. After serving his Monaco sentence and returning to the United States under a new name, Maher was later convicted of multiple crimes, including forgery and burglary. In 2025, he was sentenced to nine years in prison for soliciting the murder of his then-estranged wife, a fact the documentary presents as deeply unsettling context rather than definitive proof of past guilt.

The enduring power of the Safra case lies in its ambiguity. More than 25 years later, it sits at the intersection of immense wealth, global finance, and human fallibility. As public interest surges again, the documentary does not claim to solve the crime—but it does ask a question that still resonates: in a place built on control and certainty, how did the truth remain so elusive?

For viewers, Murder in Monaco is less about revisiting a verdict than confronting the discomfort of unresolved doubt—an unease that continues to shadow one of the most secure corners of the world.